By Niall McFadden, Guide & Information Officer, Office of Public Works.

Amongst many attractions for visitors to Farmleigh’s beautiful “Nobel” room are a series of photographs of the family of Edward Cecil Guinness, founder of Farmleigh in its modern form. Whilst Edward’s first and seconds sons, Rupert and Ernest, achieved much distinction in various fields it was the youngest of the three, Walter, who would ultimately go on to have the most varied and far-reaching career. Spanning over four decades in fields as diverse as politics, the military, amateur science and anthropology he travelled the globe, held major positions in British politics and had close relationships with some of the key figures of the time including Winston Churchill. His assassination at the hands of militant Zionist activists in Cairo in November 1944 was dramatic and news-catching, and caused shockwaves in the Middle East and around the world.

Born in Dublin at Iveagh House (now The Department of Foreign Affairs) in March 1880, Walter attended public school in England before volunteering with The Suffolk Yeomanry to fight in The Second Boer War in 1899. Following distinguished service there, he returned to England and embarked on a career in politics, becoming a Conservative MP for the constituency of Bury St Edmunds in a by-election in 1907, a seat he was to hold until 1931. The outbreak of World War 1 saw him back in Army uniform with first the Suffolk Yeomanry and then the 11th battalion of The Cheshire Regiment (as major and later brigade major). He took part in the campaign in Gallipoli in 1915 and later in France and Belgium at The Somme in 1916 and Passchendaele the following year. His war diaries reveal a thoughtful man, far removed from the image of the boorish officer common to that period. He showed much concern for the welfare of his men. In one diary entry in 1915 he writes of his “great grief” on hearing of the death of one of his men in the unit whom he had encouraged to join up. Walter defied Wartime censorship regulations to write to the man’s parents personally in advance of the official War Office notification. At Christmas 1915, he writes in the diaries of procuring bottles of Guinness and Bass beer to be distributed to the troops at Gallipoli to help them celebrate the season far from home. The diaries also reveal his low opinion of some of the top generals and he was not afraid to document the horrors and realities of the conflict. Fighting on the front line saw him exposed to danger and he was lucky to escape with his life on more than one occasion. He declined the offer of a safer position of a staff officer until near the end of the war. In 1917 he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for bravery at Passchendaele.

It was in the area of politics he became most well-known. Of his early career, there is no doubt he was very much in keeping with others of his background from that period on some of the big issues of the day. From an Irish perspective, he opposed Home Rule and spoke against reform of the hereditary powers of The House of Lords intended by The Parliament Act of 1911. Some of his early stances certainly can be seen as regressive in hindsight but the fact he was a man of ability is shown by his promotion in the 1920’s. He was first made Under-Secretary of State for War, then Financial Secretary to Chancellor of The Exchequer Winston Churchill in 1924 and finally promotion to the full cabinet as Secretary of State for Agriculture in 1925. With the advent of the Wall Street Crash and the formation of a new coalition government between Labour and the Conservatives in 1931, Guinness found himself out of the cabinet. He resigned his seat that year but was given a peerage in The House of Lords as Baron Moyne (Moyne being a reference to a family property on Lough Corrib straddling the Galway/Mayo border).

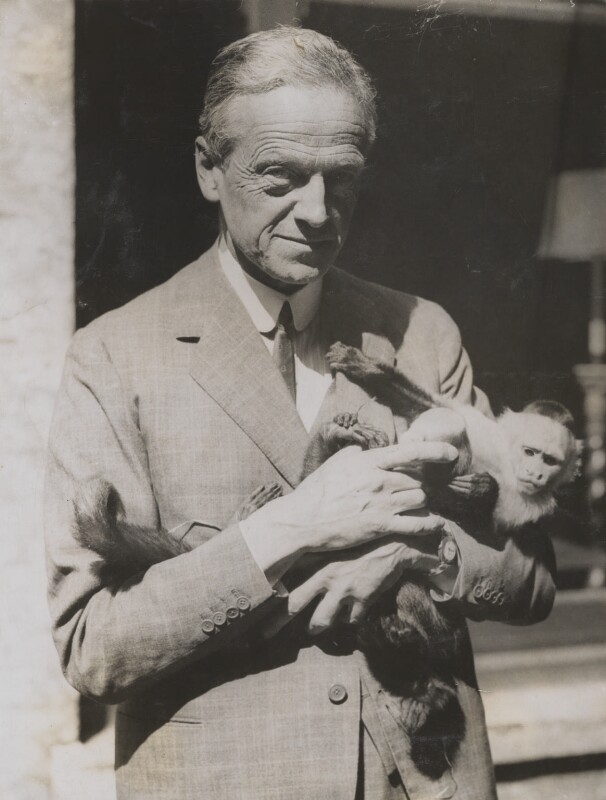

Increasingly during this period, his views differed from much of the Conservative Party led now by Neville Chamberlain, particularly on foreign affairs and the threat from Germany. Walter Guinness shared the views of his friend Winston Churchill that the Nazi party were a threat to freedom and peace and should not be compromised with. Whilst out in the political wilderness, he travelled widely, undertaking numerous expeditions by yacht to the Pacific including places such as Papua New Guinea, rarely visited before by Westerners. He wrote two books documenting his travels and explored his love of biology which he would have studied at university had he not gone down a different career route. The Moyne Collection at London Zoo lists 426 animals collected by him during his travels and bestowed on the Zoo. To commemorate his interest in science and in recognition of funding from the Guinness Family, The Moyne Institute of Preventive Medicine at Trinity College Dublin was opened in 1953.

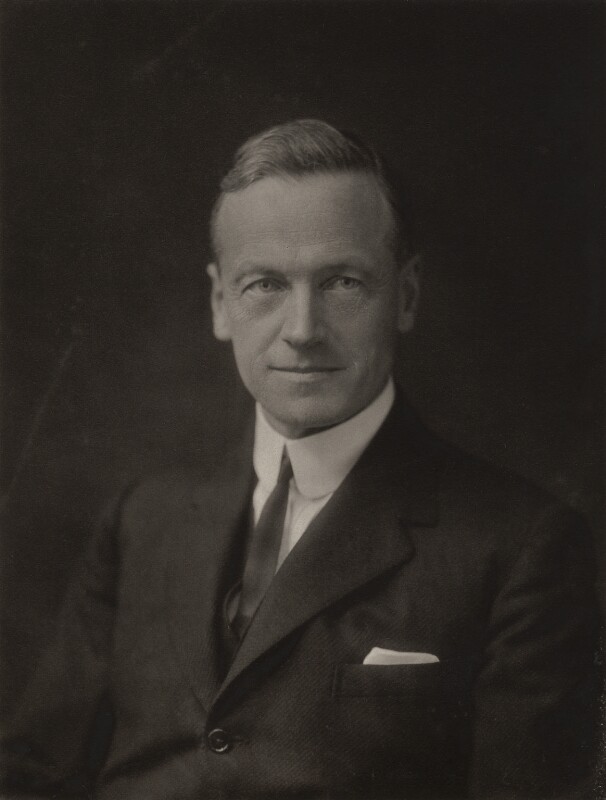

Walter Edward Guinness, 1st Baron Moyne of Bury St Edmunds

by Lady Evelyn Hilda Stuart Moyne (née Erskine) © National Portrait Gallery, London

The most dramatic episodes in his life were yet to come. On the outbreak of the Second World War and the replacement of Neville Chamberlain as prime minister with Winston Churchill, Walter Guinness was made Leader of The House of Lords and Secretary of State for the Colonies. In recognition of his knowledge of Middle Eastern affairs, he was then made Minister Resident for the Middle East based in Cairo in 1944. This gave him a seat in the War Cabinet as the post was vital due to the region’s importance. He was responsible for an area that stretched from Libya in the west to modern-day Iran in the east. Perhaps the most difficult issue he was dealing with was the question of Palestine. Britain had committed to an independent homeland for Jewish people in the region since 1917 when it assumed responsibility for the territory. An increased influx of Jewish refugees escaping persecution by the Nazis in the 1930s however caused increased tension with the Palestinian population leading to riots. As a result, limits were placed by the British on the amount of Jewish refugees accepted in the areas. Walter found himself trying to balance all the competing interests. The issue became even more acute during the Second World War with people escaping the Holocaust. There was also the longer- term issue of an independent Jewish state. Tensions were rising further. A militant Zionist group acting in the area called the Lehi (or Stern gang after its leader) had previously tried to assassinate the British High Commissioner in Jerusalem. On the 6th November, 1944 it struck again. As Walter Guinness returned to his residence from the embassy in Cairo, two of their gunmen lay in wait. As the driver got out to open the villa gate, the gunmen emerged and shot Walter and his driver. Whilst his driver died instantly, Walter survived initially but died later that night in hospital despite the efforts of the Egyptian King’s personal physician to save him. The two gunmen were chased down by an angry mob of locals and narrowly avoided being lynched before being arrested and later hanged. His death caused shockwaves internationally. Churchill was too upset at the death of his friend to lead tributes to him in the House of Commons. As much as anything, Walter Guinness paid the price for the policies of the administration he served. During his career he had displayed courage, initiative and at times independence. Ironically, Churchill had been scheduled to meet with Jewish leaders only days later to discuss the question of an independent homeland. It was taken off the agenda and not dealt with by his administration again. The issue had to wait a number more years.

Walter was married to Lady Evelyn Guinness (nee Erskine) and they had three children, Bryan (an author and playwright), Murtogh and Grania. Notable descendants include grandson Desmond Guinness, founder of the Irish Georgian Society and great- great- granddaughter Jasmine Guinness, the renowned fashion model.