by Dr Nora Moroney, IRC Postdoctoral Fellow TCD, Marsh’s Library, Farmleigh House.

The Benjamin Iveagh Library, in its beautiful wood-panelled room at Farmleigh, contains over five thousand books. Of these, only a handful are written by women. This is not altogether surprising – women have traditionally been underrepresented in literary history, especially the canon of Irish literature. They are also less likely to have been published in expensive intricate bindings, the kind collected by Benjamin Guinness, third Earl of Iveagh (1937-92).

The women writers who do feature on these shelves are an interesting group. There are seven female authors in the library – Lady Jane ‘Speranza’ Wilde, Lady Gregory, Sydney Owenson (Lady Morgan), the Countess of Blessington, Maria Edgeworth and OE Somerville and Violet Florence Martin (more generally known as Somerville and Ross). Their elite status in Ireland’s literary culture is mirrored by their aristocratic titles, most of them belonging to an Anglo-Irish milieu so familiar to the inhabitants of Farmleigh.

Portrait of Lady Jane ‘Speranza’ Wilde, 1885.

The most recognisable names are perhaps Wilde and Gregory. Jane Wilde is today best known as the mother of Oscar Wilde, but was a respected writer, translator and literary hostess in her own right. Her books here reflect her interest in Irish mythology and folklore. Ancient cures, charms and usages of Ireland (1890) appears in first edition, alongside Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions of Ireland (1887). Her works tap in to the growing awareness of local and cultural histories from the mid-nineteenth century, seen also in her husband William Wilde’s 1867 guide book to Lough Corrib (the library’s copy is inscribed to Benjamin Lee Guinness, and contains a letter from the author).

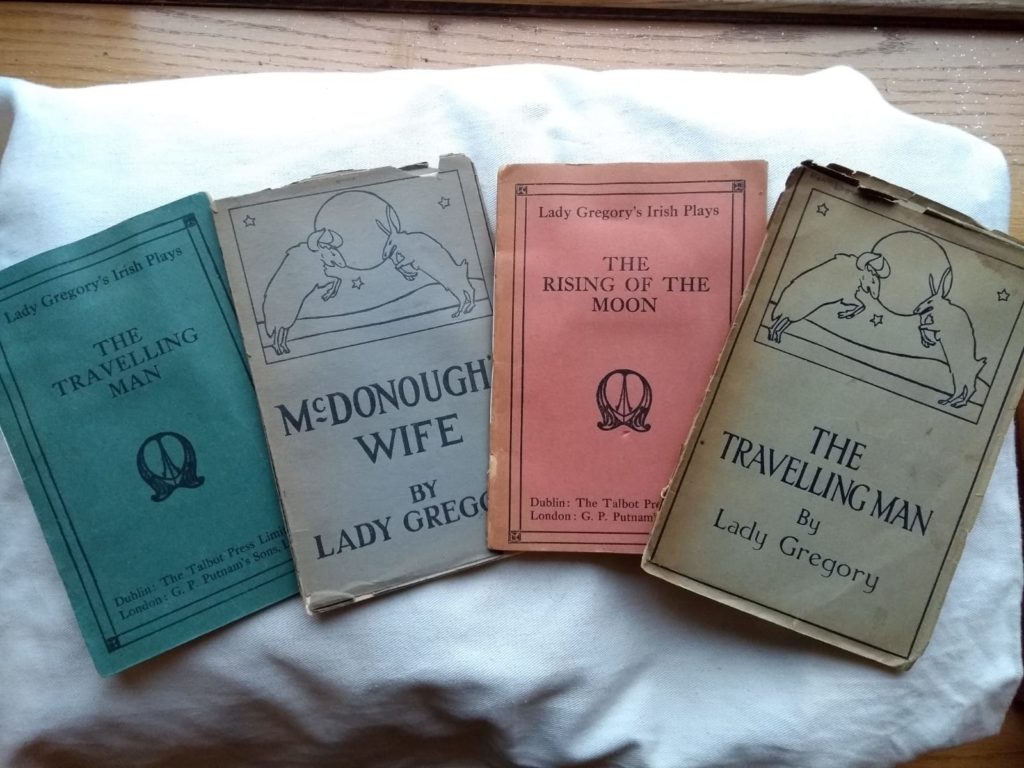

Lady Augusta Gregory, the owner of Coole Park in Galway, was a central figure of the Irish literary revival of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Iveagh collection boasts sixteen works by Gregory and many more letters, collaborations and inscriptions, tracing her influence across one of the most important eras in Irish literature. Like Wilde, her plays (such as McDonough’s Wife) also draw on the folklore of rural Ireland, and became core themes of the early days of the Abbey theatre. One of the most valuable Revival-era books in the collection is a first edition of Yeats’s Where There is Nothing: Plays for an Irish Theatre (1903), dedicated and inscribed to Gregory from Yeats and bearing her bookplate. The copy also contains five original drawings, four of them in pencil – probably by Gregory herself – representing characters in the play, and an ink portrait on the title page by Jack Yeats.

First editions of some of Lady Gregory’s plays.

Lady Morgan and the Countess of Blessington, meanwhile, were two of the nineteenth century’s most celebrated female writers. Morgan’s The Wild Irish Girl (1806) is widely seen as the original ‘National Tale’ – packaging Ireland and its culture for an English audience. Blessington, too, used her Irish charm to build a successful and well-travelled career, mixing with figures like Charles Dickens and publishing Conversations with Lord Byron in 1834. Both women were successful in the growing genre of travel literature at the time. The library holds first editions of Morgan’s books Italy (1821) and France in 1829-30 (1830), as well as Blessington’s similar The Idler in France (1841). Perhaps most interesting is a manuscript copy of ‘Railroads and Steamboats’ by Lady Blessington, describing a journey by train and boat taken in 1841, a little over a year after the completion of the London-Southampton Line. The narrative conveys the excitement of the new experience of rail travel, where the train ‘flew along, like some unearthly and demoniacal carriage, impelled by evil spirits on its mad course’.

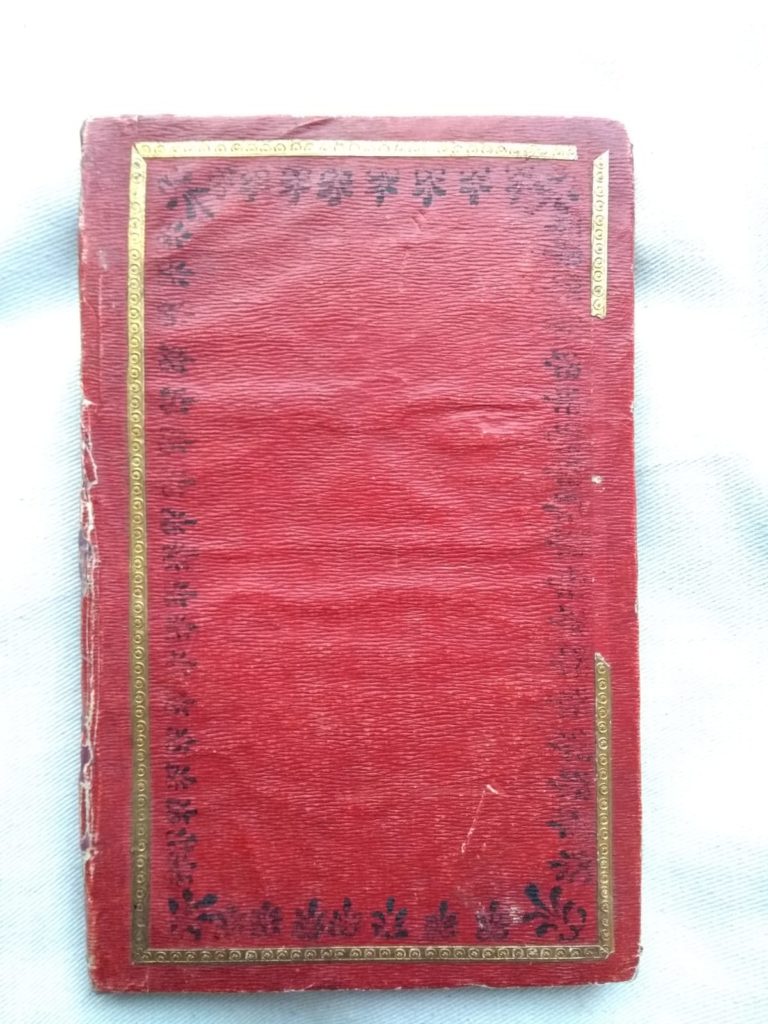

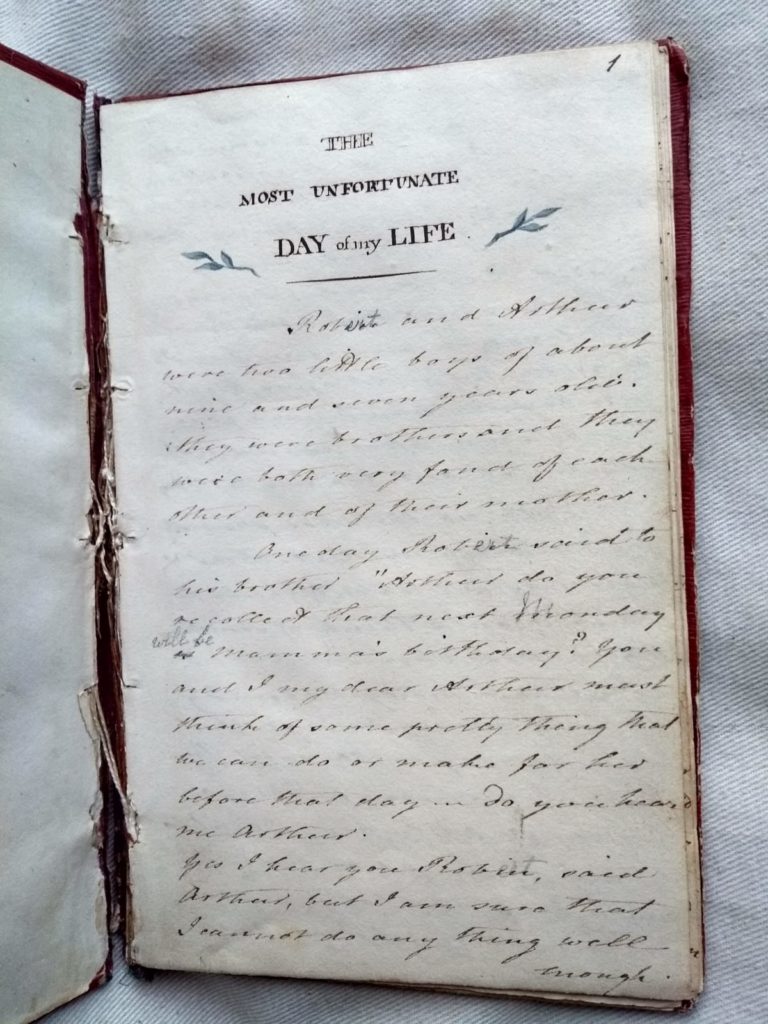

Bookending this group are Maria Edgeworth (1767-1849) and Somerville and Ross. Edgeworth was one of the earliest Irish women writers to find widespread fame, with books such as Castle Rackrent and Belinda. The Iveagh copy of Castle Rackrent is notable, as first edition copies such as this don’t have her name on title page. After its instant success, her name appeared from second edition onwards. Indeed her books, almost all of which are collected in the library, were instrumental in the development of the nineteenth century novel in Britain and Ireland. Original Edgeworth material is today extremely valuable, and one of the jewels of this collection is a beautiful handwritten manuscript of her work The Most Unfortunate Day of My Life (1819).

Front cover and first page of Edgeworth’s manuscript of The Most Unfortunate Day of My Life (1819.)

Over a century later, Somerville and Ross had a similarly long and successful career. The two women were cousins from somewhat faded aristocratic families, who witnessed the turmoil of the revolutionary years and its impact on the big house life. Following on from their early success The Real Charlotte (1894), they published over fifteen novels and memoirs about Irish life. Their entire collected works are shelved together in the library, many of them bearing inscriptions to family members and friends. Alongside these are an important collection of manuscripts and letters detailing their literary lives and travels.

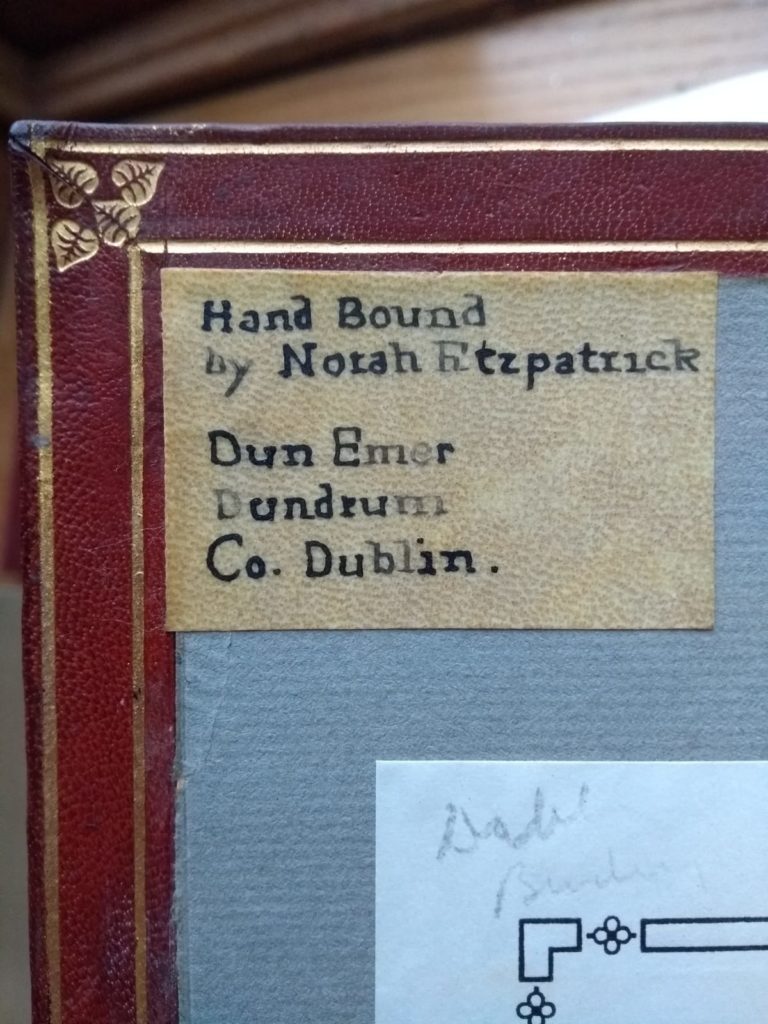

Finally, women also occur in rather unexpected places in this collection – the bindings. Iveagh collected many editions from the Dun Emer and Cuala Press: early twentieth-century publishing houses set up by the Yeats sisters and run almost entirely by women. They were celebrated for their ornate, hand-printed publications and often signed their names inside the covers. A fine example of this is a red and gold embossed edition of The French under the Merovingians (1850) held in the library.

Inner front cover of The French under the Merovingians (1850), bound by Dun Emer Press.

As these works show, women’s voices do emerge from this collection. By paying attention to the margins – literally – we can trace their influence across Ireland’s literary history, from the early Romantic era to the height of the Celtic Revival.